5. DLLists

In Chapter 2.2, we built the SLList class, which was better than our earlier naked recursive IntList data structure. In this section, we'll wrap up our discussion of linked lists, and also start learning the foundations of arrays that we'll need for an array based list we'll call an AList. Along the way, we'll also reveal the secret of why we used the awkward name SLList in the previous chapter.

addLast

Consider the addLast(int x) method from the previous chapter.

public void addLast(int x) {

size += 1;

IntNode p = sentinel;

while (p.next != null) {

p = p.next;

}

p.next = new IntNode(x, null);

}The issue with this method is that it is slow. For a long list, the addLast method has to walk through the entire list, much like we saw with the size method in chapter 2.2. Similarly, we can attempt to speed things up by adding a last variable, to speed up our code, as shown below:

public class SLList {

private IntNode sentinel;

private IntNode last;

private int size;

public void addLast(int x) {

last.next = new IntNode(x, null);

last = last.next;

size += 1;

}

...

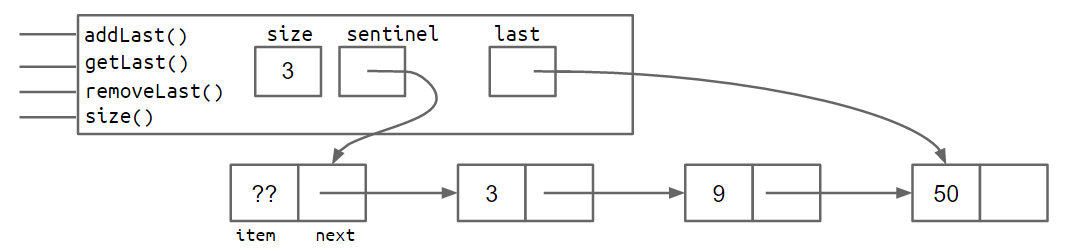

}Exercise 2.3.1: Consider the box and pointer diagram representing the SLList implementation above, which includes the last pointer. Suppose that we'd like to support addLast, getLast, and removeLast operations. Will the structure shown support rapid addLast, getLast, and removeLast operations? If not, which operations are slow?

Answer 2.3.1: addLast and getLast will be fast, but removeLast will be slow. That's because we have no easy way to get the second-to-last node, to update the last pointer, after removing the last node.

SecondToLast

The issue with the structure from exercise 2.3.1 is that a method that removes the last item in the list will be inherently slow. This is because we need to first find the second to last item, and then set its next pointer to be null. Adding a secondToLast pointer will not help either, because then we'd need to find the third to last item in the list in order to make sure that secondToLast and last obey the appropriate invariants after removing the last item.

Exercise 2.3.2: Try to devise a scheme for speeding up the removeLast operation so that it always runs in constant time, no matter how long the list. Don't worry about actually coding up a solution, we'll leave that to project 1. Just come up with an idea about how you'd modify the structure of the list (i.e. the instance variables).

We'll describe the solution in Improvement #7.

Improvement #7: Looking Back

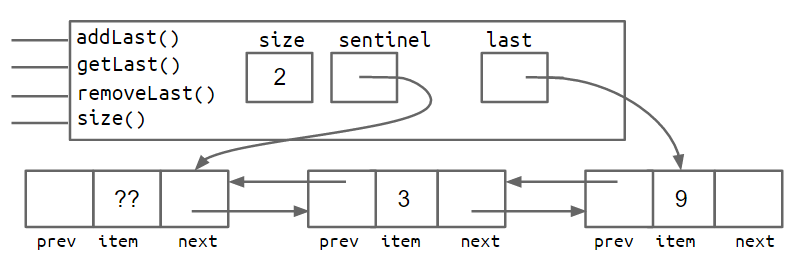

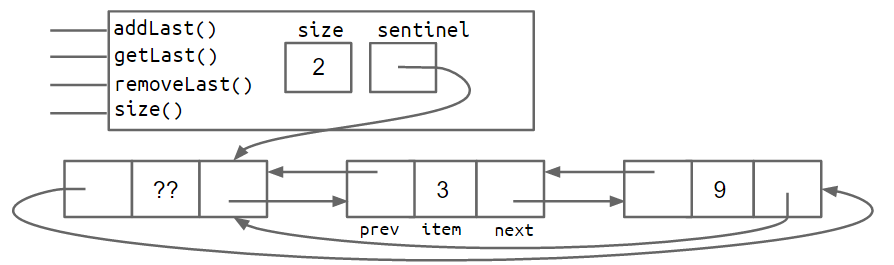

The most natural way to tackle this issue is to add a previous pointer to each IntNode, i.e.

In other words, our list now has two links for every node. One common term for such lists is the "Doubly Linked List", which we'll call a DLList for short. This is in contrast to a single linked list from chapter 2.2, a.k.a. an SLList.

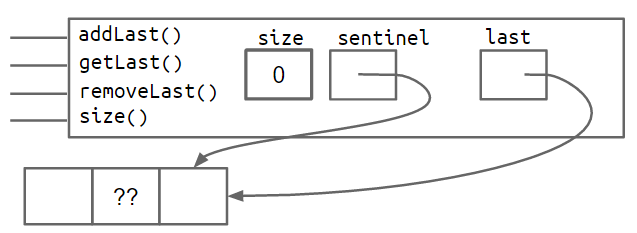

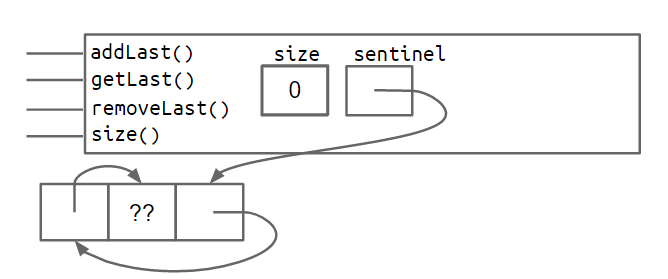

The addition of these extra pointers will lead to extra code complexity. Rather than walk you through it, you'll build a doubly linked list on your own in project 1. The box and pointer diagram below shows more precisely what a doubly linked list looks like for lists of size 0 and size 2, respectively.

Improvement #8: Sentinel Upgrade

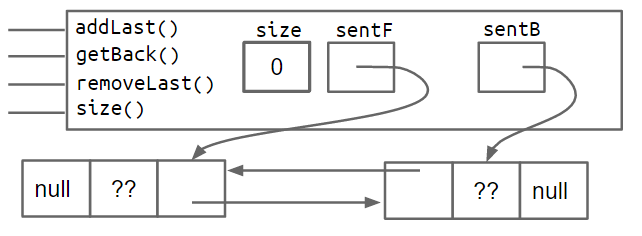

Back pointers allow a list to support adding, getting, and removing the front and back of a list in constant time. There is a subtle issue with this design where the last pointer sometimes points at the sentinel node, and sometimes at a real node. Just like the non-sentinel version of the SLList, this results in code with special cases that is much uglier than what we'll get after our 8th and final improvement. (Can you think of what DLList methods would have these special cases?)

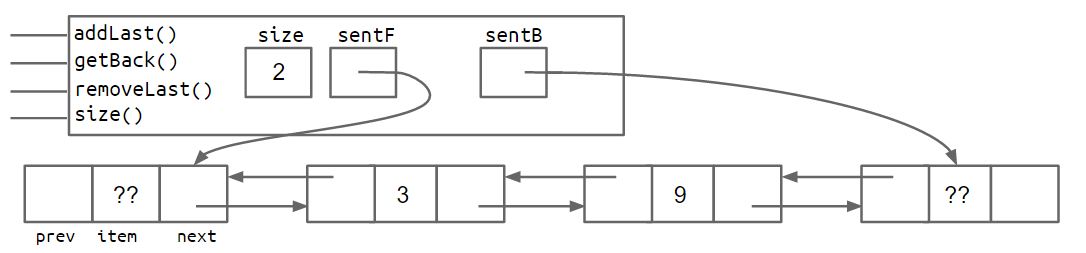

One fix is to add a second sentinel node to the back of the list. This results in the topology shown below as a box and pointer diagram.

An alternate approach is to implement the list so that it is circular, with the front and back pointers sharing the same sentinel node.

Both the two-sentinel and circular sentinel approaches work and result in code that is free of ugly special cases, though I personally find the circular approach to be cleaner and more aesthetically beautiful. We will not discuss the details of these implementations, as you'll have a chance to explore one or both in project 1.

Generic DLLists

Our DLLists suffer from a major limitation: they can only hold integer values. For example, suppose we wanted to create a list of Strings:

The code above would crash, since our DLList constructor and addLast methods only take an integer argument.

Luckily, in 2004, the creators of Java added generics to the language, which will allow you to, among other things, create data structures that hold any reference type.

The syntax is a little strange to grasp at first. The basic idea is that right after the name of the class in your class declaration, you use an arbitrary placeholder inside angle brackets: <>. Then anywhere you want to use the arbitrary type, you use that placeholder instead.

For example, our DLList declaration before was:

A generic DLList that can hold any type would look as below:

Here, BleepBlorp is just a name I made up, and you could use most any other name you might care to use instead, like GloopGlop, Horse, TelbudorphMulticulus or whatever.

Now that we've defined a generic version of the DLList class, we must also use a special syntax to instantiate this class. To do so, we put the desired type inside of angle brackets during declaration, and also use empty angle brackets during instantiation. For example:

Since generics only work with reference types, we cannot put primitives like int or double inside of angle brackets, e.g. <int>. Instead, we use the reference version of the primitive type, which in the case of int case is Integer, e.g.

There are additional nuances about working with generic types, but we will defer them to a later chapter of this book, when you've had more of a chance to experiment with them on your own. For now, use the following rules of thumb:

In the .java file implementing a data structure, specify your generic type name only once at the very top of the file after the class name.

In other .java files, which use your data structure, specify the specific desired type during declaration, and use the empty diamond operator during instantiation.

If you need to instantiate a generic over a primitive type, use

Integer,Double,Character,Boolean,Long,Short,Byte, orFloatinstead of their primitive equivalents.

Minor detail: You may also declare the type inside of angle brackets when instantiating, though this is not necessary, so long as you are also declaring a variable on the same line. In other words, the following line of code is perfectly valid, even though the Integer on the right hand side is redundant.

At this point, you know everything you need to know to implement the LinkedListDeque project on project 1, where you'll refine all of the knowledge you've gained in chapters 2.1, 2.2, and 2.3.

Last updated